This is the first installment in a series examining various narratives about Mexico's most notorious antihero: El Narco.

In April and May there were a spate of stories on social media, blogs and in the traditional press about criminal groups handing out supplies in poor and rural areas of Mexico. These stories featured images of men, cuernos slung over their shoulders and faces obscured, handing out groceries to grateful crowds of people. The gesture by the purported criminal groups was a benevolent, Robin Hood-like show of force intended to demonstrate the group's wealth and power while simultaneously endearing themselves with the communities.

Some of these scenes were almost certainly authentic. It's hard to qualify what authenticity looks like exactly, but some things that stick out are the quality of the video, the way the supplies were packaged and the appearance of the individuals handing out aid. Videos produced by criminal groups are typically low-resolution, shaky footage shot on a cheap cellphone. With respect to the way the groceries were packaged, what you might expect from an authentic criminal group would be something which takes the least effort. Plastic bags which come in standard sizes and can be found almost anywhere would probably be more likely to be used since they're the easiest to come by. As for the individuals handing them out, what you might typically expect to see is someone that looks like an average criminal group member: young, skinny and poor.

En la gustada sección México lindo y querido...

— Arturo Luna Silva (@ALunaSilva) May 16, 2020

Ahora son miembros del CJNG quienes están entregando despensas a personas afectadas por el desempleo en Coatzacoalcos y Acayucan en #Veracruz; se han formado largas filas de desempleados y madres solteras para recibir el apoyo. pic.twitter.com/pMPWxrix1v

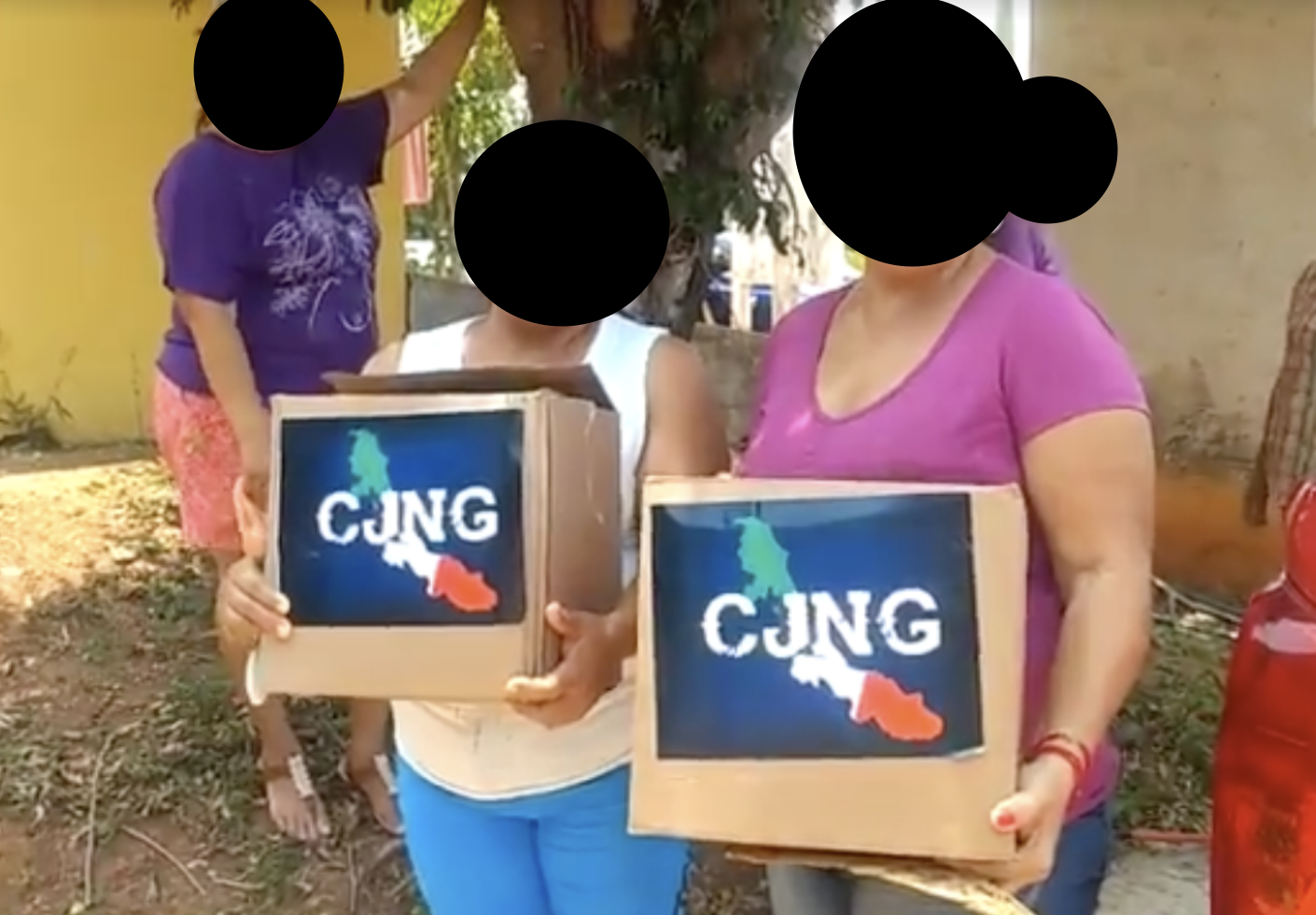

This Twitter thread from May 16 purportedly shows several associates of Cártel Jalisco Nueva Generación (CJNG) distributing boxes of supplies in Coatzacoalcos and Acayucan, Veracruz.

Looking at the pictures and video stills from the thread, there are several things that stand out right away as inauthentic.

For starters, the pictures and videos themselves are fairly high-quality, likely taken from a high-end smartphone. Doesn't prove anything, but definitely not typical. The reasons most criminals aren't usually using the latest iPhone is because 1) most of these guys are poor, and 2) the fancier a phone is, the easier it is to track. Secondly, the supplies are packaged in uniform cardboard boxes. Not impossible to get ahold of, but certainly more trouble to track down than plastic bags. One of the biggest red flags is the comically oversized, professionally printed, glossy 'CJNG' sticker slapped on the side of each box. This is where they lost me. The only person that would go to the trouble of making logos like these is someone that really wants you to think that they're CJNG. In other words, the cops. Or more specifically, the marina of the Mexican navy (SEMAR, more on that shortly). This van full of absurdly large 'CJNG' labeled boxes conspicuously featured in every scene looks like it came straight from the CJNG factory. Give. Me. A. F*cking. Break.

The funniest thing about this photoshoot is hands-down the marina pretending to be CJNG. Where do I even begin? The baseball hat with a piece of tape obscuring the Under Armour logo? The olive drab tee shirt turned inside out to hide the print which probably says 'SEMAR'? The giant smartphone in his front pocket? The fact that he's well-fed and built like someone that does PT everyday rather than someone living on a diet of ramen noodles and crystal meth? The fact that he's at least in his mid-20s (well-past retirement age for most people in the life)? Those f*cking shoes???? In summary, I would bet all of the money I have that this is a marina and not CJNG. Why a marina? Well, because Batallon de Infanteria de Marina Numero 9 is in Coatzacoalcos.

The simulation of a criminal group superseding the role of government by providing community aid in times of need posits El Narco as more powerful than the Mexican state. At times, that appears to actually be the case, like in the botched arrest of Los Chapitos on October 17, 2019, when the world saw the Mexican state brought to its knees by hundreds of gunmen in Culiacán. But why the plan failed so spectacularly isn't entirely clear. Did it fail due to the incompetence of officials in planning and executing the operation, or was incompetence playacted like a scaled up fake CJNG photoshoot? Regardless of the answer, the question is valid.

Why would a state—whose role necessarily includes projecting legitimacy and sovereignty—want the country to appear less capable than violent criminal groups? The simple answer is that the indistinguishable relative proportions of truth and fiction constituting El Narco rationalize actions and policies that would otherwise be constrained.

To be continued…